'He was like the Messiah': Larry Levan, the DJ who changed dance music forever

As a new compilation of his productions is released, Sam Richards spoke to his peers and devotees, such as Nicky Siano and DJ Harvey, who saw him move from a wannabe fashion designer to the most influential DJ of all time

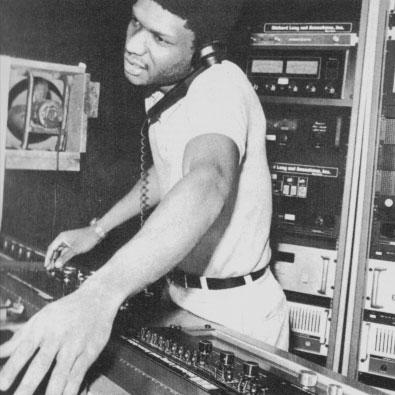

Larry Levan in the DJ booth at Paradise Garage in 1978. Photograph: Bill Bernstein / serenamorton.com

Interviews by Sam Richards

Mon 28 Mar 2016 13.01 EDT

Larry Levan was the first superstar DJ. The first to really convince the world that there was more to DJing than just playing one record after another. For 10 years from 1977 to 1987, Levan was the star attraction at New York’s legendary Paradise Garage, writing himself into clubbing lore with swashbuckling DJ sets that took in minimal underground disco, funky rock, dub and synth-pop, which foreshadowed the house music revolution. At the same time, his uncanny ability to mix and tweak records for maximum emotional impact would regularly send his devoted congregation into raptures.

Soon after the Garage opened, Levan also expanded into music production and mixing in order to create the sounds he wanted to hear in the club. His unique approach helped make stars of singers like Taana Gardner and Gwen Guthrie, and his enveloping yet propulsive productions for the likes of Man Friday and the Peech Boys remain hugely influential in underground dance circles. Many of those seminal tracks are collected on a new compilation, Genius Of Time, which is out now. Here, five of Levan’s friends, collaborators and acolytes reflect on his life and legacy.

Nicky Siano: legendary New York DJ, Levan’s boyfriend and mentor

Nicky Siano: ‘Look as his body of work, look at the mixes.’ Photograph: Peter Stroh/Alamy

I met Larry in 1973. We’d just opened The Gallery [Siano’s own pioneering Manhattan discotheque]. I’d already hired Frankie Knuckles and the second week he said: “Look, I know this kid, he’s a little bit crazy but he’s really great.” And that was Larry. He didn’t want to be a DJ at that point. He didn’t even look at the turntables. Larry wanted to be a fashion designer. So Larry was my decorator for the first six to eight months. And he spiked the punch, that was his job.

About a year into working for me, when we were closed, Larry said “Can I try to play records a little bit?” And that was the first time he showed an interest, around April 1974. Once he met Mike [Brody, Paradise Garage proprietor], Mike was like, “Larry’s my DJ, I’m gonna open a club for him.” So it was handed to him. It had a lot to do with Larry’s magnetic personality and a lot to do with how he played records. Which was basically how I played records! As a matter a fact he would use the same changes as I did, he would use the same sound effects that I did, over the same records … So he was working with a tried and true formula.

But give Larry credit, look as his body of work, look at the mixes. One after another after another. Impeccable. I’ll never forget when I heard Ain’t No Mountain High Enough at the Garage for the first time and [fellow DJ] Walter Gibbons was standing under the booth, staring at him through the whole mix because that was a record not to be touched, it was considered sacred. But at the end of the song Walter was clapping, like, “OK you did it, you really did it.”

I remember the night he played [Gwen Guthrie’s] Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ On But The Rent for the first time and it sounded incredible. I was never able to get those kind of sounds in my productions. I did not have the ear that Larry had producing. In the studio I was always worried about how much it was costing instead of tweaking the sound a little bit more. But Larry didn’t care. He’d stay there and mix for 48 hours, but he’d come out with a brilliant product. I think his strongest position was as a mixer – putting that last step on the record that made it work.

Taana Gardner: singer of several Paradise Garage hits mixed by Levan

My first-ever performance as a pop singer was at the Paradise Garage. I recorded Work That Body on Thanksgiving Day 1978, so it had to be January or February the following year when I went in to perform it live. I hadn’t ever been to the club before. My nerves were very on edge. The club was filled with a vibration I’ve never felt before, or since. I remember thinking, “What do they want from me?” But the moment I stepped to the mic there was a roar I’d never heard. I was always an odd bird, I didn’t really fit anywhere. But that night, I felt I’d found my home.

I don’t think anybody ever can explain [the atmosphere of the Paradise Garage] exactly, it’s something you had to experience. It was just a freedom … an acceptance. There’s never been anything like it before or since. The vibe was so extraordinary. I have a song called Paradise Express, and the song says: “To catch this train you don’t need no cars / Cos the depot’s the Paradise Garage / Have nothing to worry, have nothing to fear / Cos your No 1 DJ’s your engineer.” Larry was the engineer, and everybody loved the way he engineered. When you have a real good engineer on a train it’s a smooth ride, and that was Larry Levan.

I always loved what Larry did. He had his own twist. And Larry loved to work on our projects because they were always so innovative and ahead of their time. Heartbeat was so many BPMs slower than everything around – it was not an instant hit. One night Larry played Heartbeat in the Garage and it cleared the floor, I was the only one dancing. But [influential WBLS radio DJ] Frankie Crocker ran to the booth demanding to know who it was. Between Frankie and Larry, they were consistent with playing it. And then the vibe started flowing and growing and it became massive.

Larry would play until 10 o’clock in the morning. It was pitch black when you got there, and it was sun when you got out. And he didn’t just play what was on his mind, he could actually feel the pulse of the club. I remember one night, for over 30 minutes all he played was “toot toot, hey, beep beep” [from Donna Summer’s Bad Girls] and the club erupted. He had a way of feeling what the people wanted to hear. They were clearing that place out, and up and down the street to the subway, people were still dancing and singing “toot toot, hey, beep beep”! To send everybody home singing and dancing, Larry had that … not power, but I believe it was a connection.

He passed in 1992, but you could play all of his old tapes and they’d still have the same effect. And I believe that his humbleness about what he did is what carries. It’s not the arrogance of some of these DJs who feel like they have the power. Larry was always thanking me for letting him mix my records. I always felt that when I was around Larry it was his pleasure to be in my presence. Larry’s humbleness about what he did is the reason why the legacy stands.

Bernard Fowler: singer of the Peech Boys, the Garage’s ‘in-house band’

Larry was like the Messiah. People would look up to the booth and scream his name. The first celebrity DJ. There was no other place like that or anything similar. It was kinda surreal. Larry controlled the mood of the place with the records he played – or the records he didn’t play. Larry had a little rock’n’roll in him and every once in a while, people in the club would hear it. He’d throw on Eminence Front by The Who, and that was cool. Nobody else was doing that – at the time it was either/or. But Larry had a good ear, he had appreciation for a lot of music that wasn’t just club music.

The Peech Boys came together in a loft on 30th Street. We knew that if we could get Larry Levan to play our records things would get a lot easier, so we started going down to the Paradise Garage. And after a while, Larry started coming round to our loft. We’d talk about our music and if he had any ideas about what we should be doing. And when Larry came on board, everything changed.

When we recorded Don’t Make Me Wait, Larry was there behind the desk hooking up the effects. He worked on the handclaps and that became the signature of the song. We always took the songs down to the Garage to see the reaction and I remember standing in the booth and looking down when Larry played Life Is Something Special for the first time. It was amazing. He worked that crowd up into a frenzy. Suddenly it seemed like it was on the radio every other song. But what happened with the Peech Boys is what happens with a lot of other bands. There’s some success, there’s some money, and people get greedy. It really got bad. Larry was having problems with [keyboard player] Michael de Benedictus, who’d nominated himself as the mouthpiece of the group. There were some substance issues, and they had a falling out.

Years later, I ran into Larry in London. I was there recording with Tackhead and he was doing a DJ gig. So we got together and hung out. Larry apologised to me for the way things had turned out with the Peech Boys and that to me was big. After all the bullshit had gone away, we started to get tight. We even got back into the studio, recording ideas. Then one day, Larry had to go into the hospital for something and he called me. I wasn’t in, but he spoke to my wife. And I think the last conversation he had with anybody was with her. Because the next day he was dead. I was bummed about that for a long time. He was a complicated guy but overall I was happy to have him as friend. He was incredible cat, man. He was special. Crazy as hell, but very special.

DJ Harvey – Early Ministry Of Sound resident who befriended Levan in London

DJ Harvey: ‘He was born to do it.’ Photograph: Alicia Canter (commissioned)

I first met Larry at the Ministry Of Sound. I worked with him for a couple of days when he was tuning the system at the Ministry Of Sound. We’d put on a D-Train record, run down to the dancefloor and move the stacks six inches this way and a foot that way to get an even sound through the room.

Larry could convey emotion and tell a story through his selections and the way he worked a record, enhancing certain points of a track, certain lyrics. You could hear him talking to you through the music. In hi-fi world, people are trying to reproduce the performance on the record. In DJ world, the last point of the performance is the playing of the record. And he was very good at that. He was born to do it, he had a natural ability to understand the medium and purvey it in a way that allowed you to transcend your mundane life.

The last thing we would talk about was music really, because that was a given. We’d often talk about movies and fashion. We’d go shopping together. He had a sister who lived in south London, so on one of his visits to her he’d found this boutique at the end of the northern line in Morden. It was the kind of place where Nigerian taxi drivers buy their fashion. Larry was African, not West Indian, so he definitely leaned towards those fashions. He’d come out of there dressed in green snow-washed denim.

James Hillard – Horse Meat Disco DJ and Larry Levan disciple

James Hillard (centre, bottom) and the rest of Horse Meat Disco: ‘His mixes were characterised by that tripped-out feel.’ Photograph: Alexis Maryon/Publicity image from music company

He was an incredibly talented DJ. People would go and see him every week and talk about it almost like a religious experience. People worshipped him. You wouldn’t call him a technically dazzling DJ; some of his mixes weren’t seamless. But he had an ability to make people dance. There are stories of Larry identifying certain groups of people on the dancefloor and saying, “I’m going to make them lose their minds right now” – and he did. He drew on lots of different influences and made dancefloor hits out of records that other people had ignored. He definitely didn’t just play New York standards; he’d play Human League or Wide Boy Awake, he liked weird, dubby Sly & Robbie sounds.

His mixes were characterised by that tripped-out feel. A favourite of mine is his mix of a Smokey Robinson song called And I Don’t Love You, which we put on our first Horse Meat Disco compilation. It’s not an instant dancefloor filler and certainly wasn’t a big hit at the time, but it’s got that addictive dreamy sound. It combines different sounds and styles that no one had thought to put together before.

He was a maverick. He never relied on tried-and-tested hits but he knew what would work in the Garage, on that great soundsystem, to make people lose their heads. It’s the sign of a great DJ that people attribute records to him instead of the band who made them. Most DJs at the time were just playing whatever were the hot records of the day, but Larry forged his own unique sound. A lot of the DJs who helped create the international dance music scene as we know it were inspired to start DJing by seeing Larry Levan at the Garage. He made being a DJ something to aspire to on the same level as being an actor or a musician. He was one of the first superstar DJs, I suppose.

Genius Of Time is out now on Universal Music Catalogue

Comments