Sex, disco and fish on acid: how Continental Baths became the world's most influential gay club

Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol and Alfred Hitchcock all frequented the decadent New York bathhouse – as did the police who constantly raided it. Its 87-year-old founder, Steve Ostrow, explains how Continental Baths made club culture what it is today

It’s 1968. Steve Ostrow and his wife, Joanne, sit in their car opposite the Everard Baths, New York City’s most popular public bathhouse. Hundreds of people are queueing to get in. Ostrow watches on, his eyes widening. Despite its popularity, he is not impressed with the Everard – or “Ever-hard” as some call it. It is typical of the city’s clubs: sleazy, secretive, unkempt, not to mention unfriendly to its gay clients. Homosexuality is illegal in the state of New York. “Hey, Joanne,” says Ostrow, turning to his wife. “We can’t miss.”

Shortly after his stakeout of the Everard, Ostrow, an opera singer by profession, opened the Continental Bathhouse. Located in the basement of the Ansonia hotel on New York’s 74th Street and Broadway, the Continental had around 400 private rooms, a sauna, a swimming pool and – eventually – a dancefloor. Over the next eight years, it became a cultural hub for music, clubbing and queer culture, providing gay men with a safe space unlike anything that had been seen before.

This story will soon be told on the big screen. Working with the novelist KM Soehnlein, the director Aron Kantor is developing a fictionalised version of the Continental’s rich history, adapted from Ostrow’s memoir, Live at the Continental Baths.

Now 87 and living in Sydney, Ostrow looks back fondly on the Continental era. The cleanliness of the Baths was – and still is – a source of great pride. “I had been to a few clubs,” he says. “But they turned me off. They were dirty … filthy. They treated you like shit.” But at the Baths, “from the first night, there were lines around the corner”.

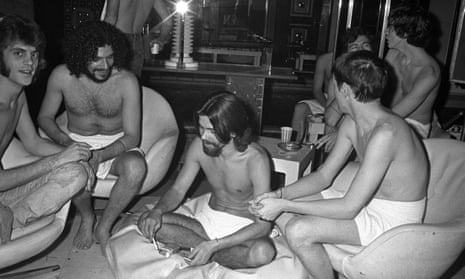

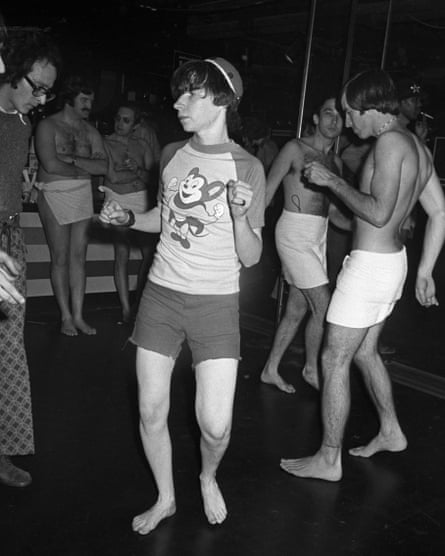

To begin with, the Baths were a social space where gay men could meet, swim, relax and have sex, but, as their popularity grew, Ostrow began booking entertainment. “I built a disco room, a DJ booth, and these special things where you put the records: ‘turntables’!” he laughs. “It was spectacular. People would dance in their towels, bathing suits, nude or anything!”

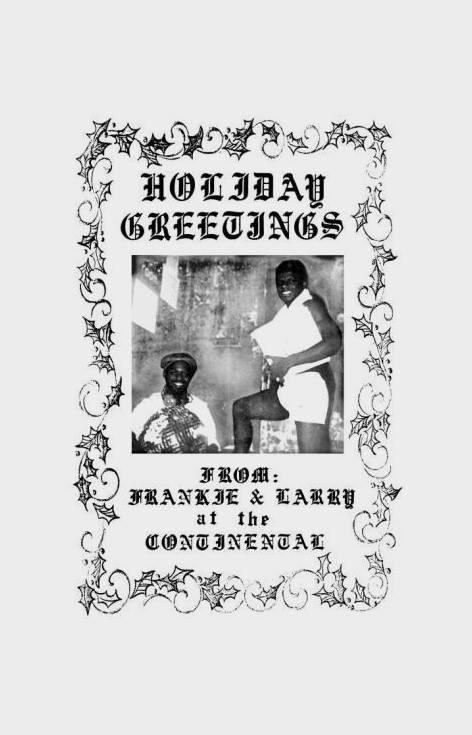

For the first time in dance music history, the stage – designed specifically for a DJ – was set. Many took their turns behind the decks, including two precocious New Yorkers called Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles. (“Very, very special,” says Ostrow of Knuckles.)

Knuckles and Levan – as well as Bobby “DJ” Guttadaro, David Rodriguez and Joey Bonfiglio – began performing at the Baths in 1974 for $25 a night. Levan became renowned for his flamboyant charisma and Knuckles for his focus and dedication. Both mixed using three turntables, a skill learned from their mentor, Nicky Siano. As disco was born, Continental DJs were breaking out classic tracks, such as Donna Summer’s Love to Love You Baby and South Shore Commission’s Free Man.

After leaving the baths, Levan and Knuckles would go on to etch their names into dance music history: Levan spent a decade playing as a resident at the Paradise Garage, another seminal venue, which opened in Manhattan in 1977. Knuckles moved to Chicago and its Warehouse venue, where he helped develop the house music sound.

In Malcolm Ingram’s documentary, Continental, Knuckles recounts one particular night at the Baths when LSD was dropped into the fish tanks, making the fish repeatedly jump out of the water for the rest of the night. Ostrow says can’t remember that incident, but recalls the club’s vending machines being full of drinks laced with acid and ecstasy. “But when I saw it, I got it out of the damn place,” he hastens to add. “If people got out of hand, we got them out and we never let them in again.”

Nevertheless, word of the Baths’ vibrant, lascivious atmosphere spread. Continental regular David Wallace moved to New York in the 70s and believes he may have come into sexual contact with as many as 10,000 people in that period. “You don’t understand what it was like in the 70s,” he says. “There was no such thing as Aids. If you went to the Baths and there were 20 guys in the steam room, half an hour later you came out and you’d had some sexual contact with at least half of the guys in that steam room. And then after another half an hour, I’d go in the Jacuzzi, then I’d go in the sauna, then the whirlpool … By the time I’d left, I’d have had some sexual contact with 150 different people.”

Though many clients only came to the Baths for one thing, Ostrow continued to book big names as entertainment. The performers ranged from Bette Midler (later nicknamed “Bathhouse Betty”) and Barry Manilow to the New York Dolls and Andy Kaufman. This, in turn, drew in famous patrons from further afield, but Ostrow won’t divulge any explicit details. “Even at this point, I’m going to respect their privacy.” Of course, not everyone came for sex. “Alfred Hitchcock came to the Baths. He wouldn’t have any sex with anyone; he would just come, watch, look at people, swim in the tub and then leave,” says Ostrow, chuckling. “People would say: ‘Who is that fat guy in the towel?’” Ostrow recalls seeing Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger and Rudolph Nureyev taking in shows.

Not all Ostrow’s memories are fond ones. Six months after it opened, the Continental was raided by police. “Homosexuality was illegal,” he emphasises. “Two men dancing together was illegal. Very good-looking policemen would come in, rent a room, get into a towel, go into the steam room and then wait for someone to touch them. And then, from underneath the towel, out would come handcuffs. Then they’d arrest everybody in the place.”

Ostrow estimates that the Baths were raided at least 200 times. Were the patrons put off? “They were in the beginning, but after they were loaded on to the trucks in their towels and all taken to the jailhouse, I would go down there and bail everybody out. They knew I always would, so they kept coming in.”

For a long time, the only way for the Continental and other gay clubs in New York to operate was to pay bribes to the police or the mafia. Ostrow doesn’t deny this, but he knew when enough was enough, and is proud of his role in helping attitudes change. “After we had the raids, we collected 250,000 signatures and marched on City Hall – there were about 100 or 200 of us – and we had the laws changed so that homosexuality in private among consenting adults was not illegal. And everything changed in the city. Everything opened up. And we were the ones who did that.”

Occurring not long after the Stonewall riots, the law change was a watershed moment for gay communities in New York. Ultimately, though, it would mark the end of an era for the Continental. Amid the steady transformation in attitudes towards sex and gay rights, more gay clubs were opening in New York. For Ostrow, that was a sign that his job was done: “It was at that point when I decided: ‘It’s time to start another club in a different place.’” So he left New York for Montreal, where he opened another bathhouse. “We had the same problems we had had in the New York one,” he laughs. “And we had the laws changed there, too.”

It’s heartening and remarkable that this married, entrepreneurial Australian opera singer was one of the most vociferous advocates for gay rights. “Let me explain to you: I am not gay, I am not straight, I am not bisexual, I am not asexual. I am a sexual person and, to me, it’s either good or bad – and why give up 50% of the population? I have slept with some of the most beautiful people in the world and I’ve never hid it from anybody, not my wife, not my family. That’s who I am.”

Asked about the Continental’s eventual demise, he pauses to flip through the pages of his autobiography, Saturday Night at the Baths. He reads from a chapter detailing his return to New York City in the mid-70s: “‘But even as I was trying to rekindle the spark in my mind, I was stepping over bodies passed out in the hallways. The smell of acid and the acrid taste of angel dust permeated the place. Stoned-out bodies were crushing into me as I walked, needles and syringes littered the halls. The hard-drug era had hit New York and it was not a scene that I could live with.’”

And so, in 1976, the Continental closed. In spite of the Aids pandemic that developed over the next decade, Wallace is unequivocal about the Baths’ legacy: “I’m unapologetic about what we did in the 70s,” he says. “We earned it. We faced such strong and harsh discrimination that to be able to completely let go and revel in who we were, I think, was very necessary.”

The sanctuary that the Baths provided for gay men became the blueprint for nightclubs everywhere; spaces where social conventions and rules seemed not to matter, and where people could escape their normal lives – and express themselves freely and safely – regardless of their sexuality. Disco and house music owe a huge debt to the Baths, not just because two of dance music’s oldest innovators learned their craft there, but because the sexual abandon running through the genre became part of its DNA at the Continental.

Today, although the promiscuity of the dark rooms at Berghain in Berlin and the towel-clad DJs at Glastonbury’s Beat Hotel may conjure memories of the baths, the like of the Continental’s pure, naked hedonism has never been seen since. “If they came back tomorrow,” says former patron Wallace. “I’d be back in a heartbeat.”

Comments