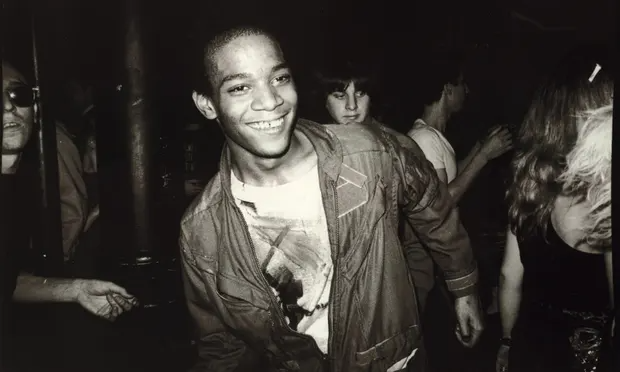

Crossing genres: a dancer at the Mudd Club in 1979. Photograph: Jean-Michel Basquiat/Barbican

The timing and location of the night’s entertainment – Grandmaster Flash at House of Yes – was entirely coincidental. On the eve of a week that would see New York City host a handful of events to celebrate and spotlight the release of Tim Lawrence’s new book, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983 – a study of what the author convincingly identifies as the city’s “cultural renaissance”, when hip-hop, new wave and dance music collided in clubs like Mudd and the Paradise Garage – one of the book’s characters was making a rare Brooklyn appearance at a space in Bushwick.

Though there’s rarely a lack of nighttime activity in the city that supposedly never sleeps, on paper it seemed like an especially great match. Unlike many New York clubs in the post-Rudy Giuliani era, House of Yes tries hard with its musical bookings, setting and entertainment acumen. Billing itself as part disco, part “circus theatre”, it features DIY décor, psychedelic projections, dressed-for-cabaret employees and an audience always ready to let loose.

Flash, meanwhile, is riding his third wind. In the mid-1970s, he helped perfect record-scratching as one of the cornerstones of the Bronx culture that came to be known as hip-hop. Now he is one of the executive producers of The Get Down, Baz Luhrmann’s colorful Netflix show that recasts the creation myth of rap and modern DJing as a fairytale musical. (And is a wonderful fact-meets-fiction preamble to Lawrence’s historical account.) So, while Flash’s stock as a local legend never fell off, it’s been a minute since it paid such high market dividends.

Understandably, the packed House of Yes crowd – an impressive congregation of young and old, black and white, straight and gay – went wild. Flash’s skills at cutting up records, and his interpretation of the cross-genre flow at the heart of the city’s original sound (disco, rap, funk, dance-punk, Latin, mutant electronic, all in the mix) were rapturous and timeless.

The scene played out like a simulacrum of the very bygone moment that Lawrence’s book documents. Reading Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor as a clubber in the city is to reflect not only on what’s been lost over the past three decades, but on how the sounds, events and characters at the center of Lawrence’s story still influence NYC’s nightlife. At House of Yes, one of this tale’s endless postscripts played out as real-time legend. In fact, through sheer circumstance, over the course of a single week in October 2016 you could watch and listen to urban folklore cement as history. Better yet, you could dance to that transformation.

“There was always a sense of New York in my imagination,” said Lawrence in one of our numerous conversations during his visit. The wiry 49-year-old may have grown up in the London exurb of Winnersh and teaches cultural studies at the University of East London, but there’s little question that New York’s late 20th-century nightlife has served as his muse. Life and Death is the third of Lawrence’s books about the city’s rhythms, joining the disco scene-redefining Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music, 1970-79, and the quasi-biography, Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-92. He also credits the city’s house music scene for his initial focus on the meaning of the dancefloor.

Lawrence first escaped to New York in the early 90s at a sensitive time in his life, following the sudden death of both parents and an early crisis of professional faith at BBC Newsnight. He studied a doctorate in English literature at Columbia University by day, and clubs by night. Love Saves the Day began as a dissertation on house music and postmodernity, mutated into a quickie book about dance music culture, before his research brought him face to face with the then little-known story of a “musical host” named David Mancuso, his private weekly gatherings at a Soho loft, and all the DJs deeply influenced by it (including the legendary Larry Levan, and father of house music, Frankie Knuckles). That party, nicknamed the Loft, basically launched global DJ and club culture; and in presenting its details, Lawrence suddenly had a career documenting the founding corner of contemporary dance music.

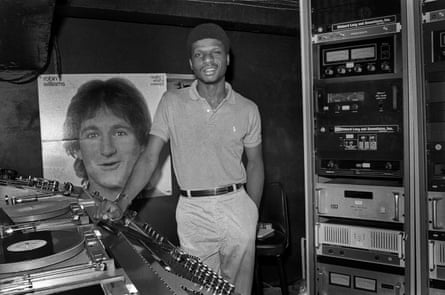

Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor began as another attempt to write that history of house, but ended up as a 500-page dive into a three-year period that exemplified “the melting pot idea that had been synonymous with New York, yet hadn’t been written about”. Popular history claimed the city’s dance scene died under the strain of the forces that killed the disco craze. Yet as Lawrence writes, the influence of Levan and his club, the Paradise Garage, was already being felt at “art-punk discotheques” like the Mudd Club and Danceteria, where DJs such as Johnny Dynell and Mark Kamins were creating a new mix for a new, mixed audience.

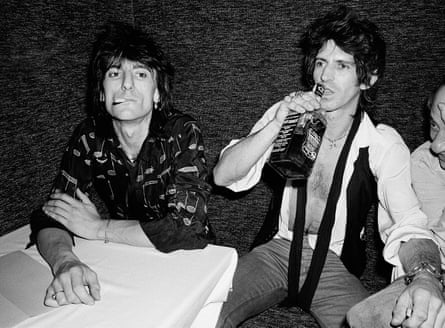

The Garage, meanwhile, was home to not just the gay, black dancers historically placed there, but also young art-punks and nascent hip-hop kids, whose music found life on Levan’s turntables. The records that came out of these borderless scenes soon became the soundtrack of the entire city and beyond, with Blondie’s Rapture, Afrika Bambaataa’s Planet Rock, the Peech Boys’ Don’t Make Me Wait and Madonna’s Holiday effortlessly crossing genres, cliques and, soon, oceans. New York club music had gravitas, with everyone from Bowie and the Clash to New Order and Herbie Hancock pulled into its orbit.

As Lawrence writes, the Downtown community’s cross-cultural collaborative spirit was not limited to clubs. The East Village’s Fun Gallery, co-founded by arts doyenne Patti Astor (one of the stars of the first hip-hop film, 1982’s Wild Style), presented the Bronx’s finest graffiti writers next to future fine-art legends Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Around the corner, the budding British impresario Reza Blue and Michael Holman, Basquiat’s bandmate in the no-wave group Gray, began throwing a weekly party at the Second Avenue club Negril that brought together the DJing Bambaataa, his Zulu Nation MCs, breakdancers and the Fun Gallery’s graffiti writers. Haring, meanwhile, was also painting murals on the walls of Danceteria and the Garage, when not helping the actor and performance artist Ann Magnusson program multi-sensorial happenings at Club 57. According to Lawrence, such creative intermingling had few precedents.

“The research suggested that there were a lot more connections between these scenes than was supposed historically,” he said. “I started to get a sense of the Downtown scene, of different art coming into this moment, of an interesting coalition of artists, musicians, choreographers and DJs. The whole artistic world seemed to be descending upon downtown New York.”

It didn’t last long. Lawrence dug into the three years between the decade’s dawn and the oncoming midnight of the crack and Aids epidemics, before Ronald Reagan’s neoliberal policies and Manhattan’s first real-estate boom took hold of New York’s cultural life. Like The Get Down, Life and Death unearths a golden moment when living was cheap, the crowds diverse, the community strengthened, creativity mutating and freedoms flourishing.

“The mythology was that New York was this hellhole of dysfunctionality, crime, murder, and garbage piled on the streets,” says Lawrence. “Yet to a person every one I’d speak to would say that far from uninhabitable, they’d never want to leave it. Every single night something was going on that seemed essential.”

“We did not want to go out to see something – we wanted to be a part of something,” said Johnny Dynell. He was seated in a seminar room at New York Universityon a drizzly Saturday afternoon, decked out in a leopard-print suit and lightly tinted shades, imparting wisdom to a gathering of grad students, zine writers and ageing bohemians treading memory lane.

A lesser-known character in Lawrence’s book, Dynell has been one of the Downtown’s connectors for nearly 40 years – DJing at the Mudd Club, Danceteria and Area; recording the 1983 electro-rap cult single Jam Hot (still sampled regularly); and, in the 1990s, with his wife Chi Chi Valenti, creating the weekly party Jackie 60, one of the city’s last 20th-century hurrahs in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, not yet gentrified. Dynell still plays around town, but on this weekend, he and a coterie of other artists and gallery owners, DJs and musicians, writers and editors, club owners and scenesters, were detailing the circumstances of Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor to a rapt audience. They were also reaffirming a set of values by which the city of their era lived – and, at times, still tries to.

Dynell’s panel, entitled Lifecycle of the NYC/Downtown Party Scene, was part of an all-day symposium at NYU that placed Lawrence’s book in broader historical contexts, one of 12 events on the author’s one-city book tour. Those included panels at three institutions of higher learning (NYU, CUNY and Columbia), book-signings at three club nights (the Loft, 718 Sessions and Better Days), talks at two galleries (Howl and Steve Harvey) and two record stores (Rough Trade and Superior Elevation), as well as one museum presentation (at MoMA, which hosted a panel after a screening of writer Glenn O’Brien’s majestic lo-fi film, Downtown ’81, starring Basquiat). Simply following the author’s itinerary was like getting a master’s primer of the city’s recent cultural accomplishments.

As the discussions of long-gone clubs gave way to movement on living, breathing dancefloors, the weight and spotlight of the city’s history could be felt everywhere, in the crowd and in the DJ booth. At times, it seemed a continuation of the classic New York story – one that was interrupted by Mayor Giuliani’s zero tolerance policies of the 90s, which included a moral crusade on nightlife by excavating and enforcing a race-dividing civic ordinance from the 1920s called a cabaret license – at others it was a brand-new one with familiar roots. The last 30 years have seen the city’s meaningful party scene on the brink of extinction – during one of the panels, Krivit put the number of cabaret licenses issued during the early 80s at 4,000; in 2016 it is around 120. The insights of Lawrence’s book provided a reflection on the state of the party and the purpose it serves.

Many participants of the Life and Death “tour” came to that week’s installment of the Loft, at 46, the planet’s longest-running classic club night. Though no longer a weekly or commandeered by Mancuso (that night’s DJ duties were split by Douglas Sherman and Colleen “Cosmo” Murphy), the Loft has retained a utopian, communal private-party vibe unlike any other, an older, mixed-race clientele, and an aspirational old-school positivity in its music and atmosphere that in America 2016 comes in extremely handy. (The party took place the night of the second presidential debate, which made Sherman’s selection of Sympathy For the Devil beyond pointed.)

By contrast, the same evening marked the end of the 13-year weekly run of DJ François K’s Deep Space party at Cielo, in the Meatpacking District, which in 2017 is moving to Output, a Berlin-style club in Williamsburg. François Kevorkian is one of the New York’s beloved dance music elders, bridging today’s city to the one depicted in Life and Death (he rose to prominence as a DJ and remixer in the early 80s), continuing to champion musical multiplicity, balancing new and old (at his Cielo swan song he presented Scuba, a popular British DJ who plays minimal techno). François’s long-cultivated following pursues the DJ’s sonic whims wherever it takes them.

Deep Space is a party that, like the Loft, could be classified as much as a community social as a rave – it took place on Mondays and had free entry before 11pm. Yet, what changes when you leave a longtime residence? Economics for one – but also demographics. Whether it’s the clubs or the thriving warehouse scene, youth and internationalism rules Brooklyn nightlife, alongside layers of social privilege. And where Life and Death-era musical programming actively attempted to cut across genres and audiences, today’s club nights are more tailored to individual sounds, textures and BPMs. Nowadays, the notion of a DJ running the gamut from dub to hip-hop to disco/house to techno to African sounds, playing to a large crowd that takes it all in, is less norm than its own peculiar lane. The origin of that lane is the New York described in the pages of Lawrence’s book.

Another pair of parties that took place during Lawrence’s week here directly reinforced this lineage. Both were DJ sets by older English men that lasted upwards of six hours. One featured DJ Harvey, who spent a few years in New York learning his craft at the feet of Levan. The other took place in a Bushwick warehouse, and marked the long-awaited return of Andrew Weatherall, who came of DJing age in acid-house London and Manchester (helping produce some of that era’s greatest records) and continues to mix moods tinged with dub and psychedelia. Both sets were epic exercises of form, stamina and musical arc, featuring records beyond simple classification. And audiences that were hard to pinpoint too – more Caucasian and younger than at Flash, but hardly monochromatic, ready for a long haul, and, to echo Dynell’s self-assessment, determined to be active participants rather than tourists. These were one version – the best version – of a new New York dancefloor.

“Emotionally, critically, intellectually, it’s hard to say that New York is the kind of mecca for dance music that it was in the 70s and 80s. Then, people came here from all over the world on pilgrimages,” said Lawrence. “It feels like times have changed. But in a way that is because of New York’s success; because its influence helped grow dance scenes all over the world. This is a good thing. But as word was spreading, New York had a difficult period.”

To simultaneously participate, observe and process history through all of one’s biases is a difficult task. To do so during late nights, in dark, sensorially overwhelming clubs, keeping all of one’s faculties intact makes it more so. It may be why real-time critical context for club music has always been rare. Yet what Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor makes acutely obvious, as both volume and prism, is not just the cultural value of the city’s party scene, but how it also serves as a moral compass – and how it still can.

“My sense of it is that there is a will in New York to bounce back [from] the low point of the Giuliani period,” Lawrence added. “We’re seeing that difficult period shifting into something more engaged and hospitable. It’s clear that there are people who are invested [in the scene], and want this to become even more re-energized.”

Time to (re)build.

Comments